What Can Airlines Do To Maximize Profits? A Thought Exercise

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome onboard Flight 4C7. If you’re going to Curiosityville, you’re in the right place. If you’re not, you’re about to have a curious flight. Flying time to Curiosityville is 14 min 23 sec. Meals/Refreshments will be served during the flight.

I ask that you please fasten your seat belts and secure all baggage underneath your seat. Please turn off all personal electronic devices, including laptops and cell phones (to avoid distractions while reading this) Thank you for choosing Campolargo Airlines. Enjoy your flight!

Let’s start by trying to understand the question, “What can airlines do to maximize profits?”

I saw this question on Twitter and my mind started running to come up with the best possible answer. This question is fascinating because it involves a lot of different thinking exercises such as simulations, probabilities, evaluating current situations, and making the best possible prediction.

The travel/tourism business is interesting because it largely deals with people’s emotions and decisions, including even our supposedly “rational” part.

This question at first looks simple, but once you are getting ready to depart (answer the question), you notice that more passengers come aboard (more layers/complexities show up). The pilot/captain (you, the reader) might wonder how many passengers (layers/complexities) is the most the airplane can hold.

The initial question was: to maximize profits, should airlines increase or decrease their prices? If you have taken an Econ 101 course, you might be familiar with this question, you might even think about the supply & demand curve and possibly the type of elasticity.

Let’s evaluate the two different scenarios involving prices. Imagine you’re the CFO of a major airline, and your job is to maximize profits.

What are you going to do, CFO?

-

Lower Prices: this is what most airlines do when they want people to book more flights (increase quantity demanded). This decision is made under the assumption that people are interested in traveling and lowering prices should help to make that decision quicker. Pretty simple, right?

-

Higher Prices: this is the case when the date is close and/or approaching and airlines raise prices because there might be some urgency (such as a business meeting) to get to a place quickly no matter what the cost might be. In economics, you might say that the elasticity of demand is shorter, so it makes sense to raise prices.

The two scenarios above are, mostly, the standard of how the airline business and revenue management are operated. The question becomes more interesting when more passengers get aboard (more layers/variables) such as someone named a virus.

At the moment, the demand for flights has gone down because of a new virus (COVID-19). This virus has restricted travel to and from different countries and people are panicking, which as a result led to thousands of cancellations.

Airlines have the option to increase, decrease, or leave prices unchanged. Prices are important because they play a major role in people’s decision-making. Therefore, helping increase or decrease the interest and demand (or as Econ people call it, “quantity demanded”).

What should airlines do now to maximize profits, considering a significant decrease in demand?

-

Lower Prices: this is the option that comes to mind to most people, and this is what airlines typically do to get people to book more flights. However, the situation has changed with the virus (COVID-19) and people are not booking as many flights. If airlines lower the prices, people will not travel anyway, so why lower the prices? Here, the airline would lose money because lower prices are not attracting more people to travel and a few limited numbers of people are taking advantage.

-

Higher Prices: this could be a controversial option, and one that one does not think about after a while. Why not raise the prices? If people will not travel at lower prices, why would they travel at higher prices? Lowering/Raising prices will not attract new travelers, the only thing that would make someone book a flight would be an extreme need such as an emergency or even a meeting. This person would normally pay whatever price the flight is at and lowering prices causes a loss of the opportunity cost for the airline. Leaving prices unchanged or even increasing them would make the business a little more stable.

Increasing prices is what airlines normally do when the flight date is approaching. Airlines take advantage of the lower elasticity of demand as the date approaches.

What are you thinking about now? Lower or higher prices?

Oh, wait! There are still more passengers (more layers) getting aboard. Lowering the prices will not attract new people because they are scared or do not want to travel. By lowering prices, there are a few people who would get interested. This number, though, would be minimum. Higher prices would automatically disinterest the number of people who might have taken advantage of lower prices.

By raising the price, the airline can take advantage of those people who need to travel anyway, no matter what the circumstance is. One answer is predicting the number of people who might get interested in booking the flight at lower prices and predicting the number of people who have the urgency to travel so higher prices would not affect that person’s choice. How can airlines calculate this?

Let’s explore this concept.

If airlines can find that balance or equilibrium, we might arrive at an interesting place (or answer).

Before we do that, we need to understand that filling a plane does not mean the airline is doing well or is profitable. There are other factors such as fares and costs. Airlines calculate the Passenger Load Factor (PLF) to determine the effectiveness to use available seats for revenue generation. The PLF is interesting because it takes into account variables such as revenue passengers, airline staff, passengers flying for free, mileage redemption passengers, goodwill tickets, among many others.

Once we’re able to understand how airplanes fill planes, now let’s explore a very important aspect in the aviation industry, price on demand (Price Elasticity).

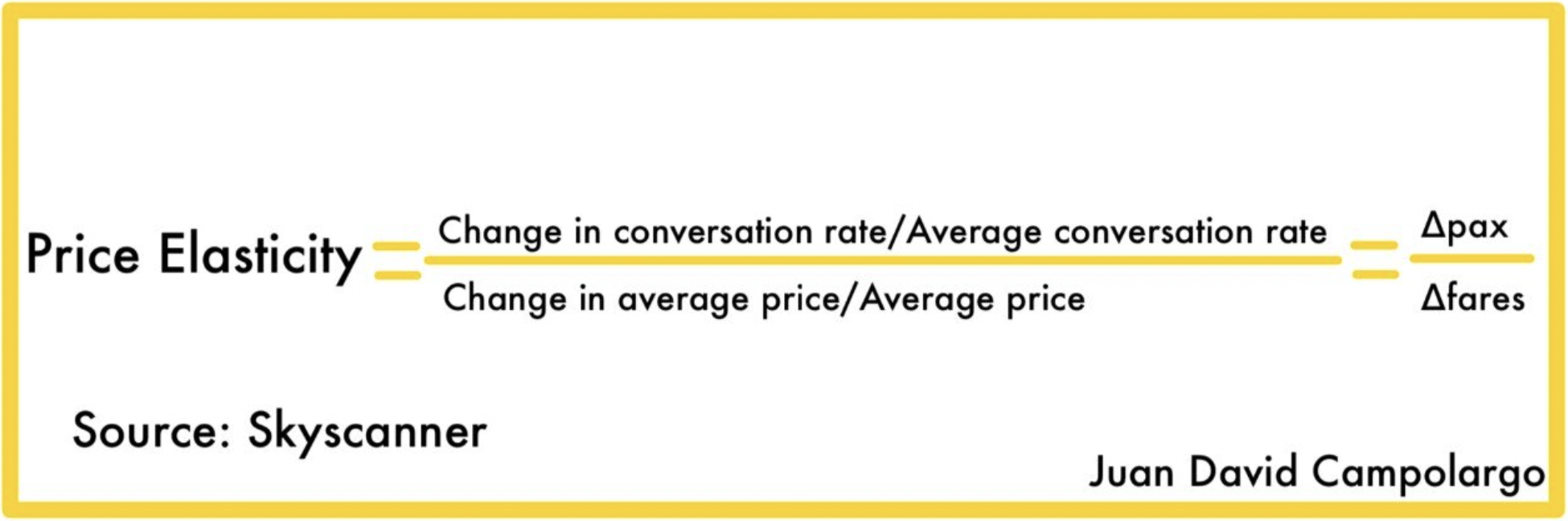

Price elasticity is the representation of how many more passengers would fly if the price drops by a certain amount. Understanding price elasticity is highly important for the airline industry because it determines choices such as multi-billion dollar orders, type of aircraft, and significantly reduces risks from any airline’s business plan.

The price elasticity is a fascinating concept, and sometimes it’s difficult to calculate. For instance, price elasticity is calculated from the number of people who did not end up traveling at a certain price point, rather than those who did. Airlines used complex algorithms to measure the number of passengers who have flown, but most models do not count the passengers who did not fly.

Calculating the number of travelers searching for a route who choose not to travel is the best sign of how satisfied users are with current options offered. When someone is deciding to book a flight, they see the different airlines and the only differentiator is the price.

However, calculating this number would have been nearly impossible to calculate without the help of search engines that provide this data.

Skyscanner did a very interesting insight study where they calculated the price elasticity. They looked at whole year data, each origin and destination, average price selected for travel during the period and the click-through rate for that same week. Then, they compared the change in conversion to the average conversion over the year and the average price to the average price during the year.

As I mentioned above, one premise of the low-cost model is the ability to increase demand. This new demand is composed by 1) the increase in interest through marketing and 2) a higher conversion of travelers interested because of lower prices. It’s also important to highlight that the total revenue of a flight is the product of the number of people that booked, multiplied by the average fare per booking.

Price elasticity is valuable to airlines today because it helps them make better decisions, understand where opportunities are and calculate profitability.

Airlines have an incredibly challenging task, which is to find a balance between prices and demand. If Airlines charge too much, people will pick another airline. If Airlines charge too little, profits margins are squeezed. To calculate this, airlines hire data providers on price and schedule information, market specializing in booking, and some of them even show future demand.

Calculating the price elasticity using new methods such as collecting the data from search engines has revolutionized the airline and the travel/tourism business. Airlines can test with different prices and calculate the right price accurately. I didn’t think calculating this number would be possible, but well...with the help of technology, nearly everything is possible.

On the Air

Airlines can predict and have the right price that meets the demand of who will travel at lower prices and those who will travel at higher prices. However, this isn’t just a simple demand question.

Other factors that are at risk include reputational damage, loyalty, long-term relationships, and losing spots at the airport.

For instance, their brands will suffer if they increase prices during the crisis. Airlines are very focused on long-term customer relationships, and the most loyal/frequent customer may be the ones flying.

These long-term relationships are sometimes built around human reciprocity norms, so it is important that the customer feels the airline is treating them fairly. Some may even consider achieving long-term profits through goodwill or short-term profits by increasing prices.

Another factor is that there will probably be a lot of cancellations or very few bookings. If airlines are truly interested in their loyalty, they might even consider offering future credit to those who have booked to give rise to more loyalty and even help reduce the spread as people would know that they could travel after the virus has been controlled.

Even if airlines would like to be nice to their customers, there are fixed costs such as fuel and labor (sometimes with unions) so they might run fewer and more expensive flights. Many flights have to continue with few or without passengers (these are called ghosts flights) to keep air slots at airports. In that case, fuel is a fixed cost and if demand has contracted, and is steeper, lowering the price when in the elastic portion of the demand curve would increase revenue. But if they have to fly anyway to keep airport slots, they might as well try to minimize losses by filling flights using lower prices.

Airlines might want to try lowering prices, but some of them (mostly in Europe) do fuel hedging, which limits their ability to lower prices. Fuel hedging is the use of financial instruments (like options) to guarantee fuel prices or keep fuel prices stable. Here is where it gets interesting, Oil prices have decreased way lower than the hedges. Now, airlines have two problems, 1) They have to fill the planes with the fuel price agreed in the hedge, which is higher than the market. 2) In many financial instruments, they cover when prices go up, but you have to pay a premium when prices go down. Airlines would have to negotiate with the banks to not have to pay out a reverse hedge.

Or perhaps, they should just offer free seats to get public goodwill as they need to be bailed out (just kidding, mostly).

Cruise Ships are not in the air, but...

If choosing with airlines was difficult, choosing with cruise ships will be 10x more difficult.

The cruise ship business is more complex because there’s basically no elastic demand and they have a lower elasticity of supply. Airlines may have two alternatives (increasing or decreasing prices) but cruise ships, not really. Leisure traveling would be depressed as governments close borders or restrict travel. Higher or lower prices would mean nothing with no demand, so lowering prices won’t attract people, and higher prices would be… foolish.

The cruise ship industry will fundamentally change after COVID-19. Mainly because of poor circulation in cruises, thus substantially increasing the risk to be infected with diseases.

Somehow, we landed the plane…

Ladies and gentlemen, we have just been cleared to land at the Curiosityville Airport. Please make sure one last time your seat belt is securely fastened. Thank you.

Analyzing these scenarios is like playing a game such as chess, where a lot of simulations have to take place in your head to arrive at the best possible decision. What determines how good my answer isn’t the result I get after I decided, but rather what the other outcome would have been if I had chosen the alternative option.

How can we simulate and come up with all possible scenarios? The answer is that it is very hard or nearly impossible to do so, but we can use statistics and probability to make a decent decision.

When I first attempted to answer this question, I knew little about the airline business and how many decisions would be possible as well as the possible outcomes.

Decision-makers do not have a simple task as we may think, and I hope that not only these decision-makers but you (the reader) take decisions calmly and always evaluate what the other possibility would have been after each decision is taken, that way we might reduce our losses. We might think we’re so smart, but if something happens and we are wrong, our plane might not land safely and that would not be ideal.

...

If you’re into interesting ideas (like the one you just read), join my Weekly Memos., and I’ll send you new essays right when they come out.